German kitchens used to have a decorative shelf with a set of pots, neat and tidy, filled with three essentials for a clean home: soap, sand, and soda. Although English-speaking countries never had a special storage unit like this, and didn’t think of the “three esses” as a trio, they also made much use of sand and soda as well as soap.

Antique wall-hung shelves with their three containers appeal to collectors in the USA, not just parts of Europe. The most attractive to me are the ones ornamented in folk art style with full-petalled pink roses and curving outlines. Traditional German lettering adds character too.

They all seem to be made of enamelled sheet metal and belong to the first half of the 20th century, or possibly the late 19th too – the heyday of enamelware. If you know when these first came into use please do add a comment. The early 20th/late 19th century dates would match with cleaning and washing methods in that period.

Washing soda in the late 19th century was factory-made and quite affordable. Among other things, it helps with laundry and with taking out stains from wood, and is simple enough to be seen today as a “green” product. Soap, like soda, was quite plentiful by 1900, not too expensive, and was available in powder or flakes suitable for filling a nice enamel pot.

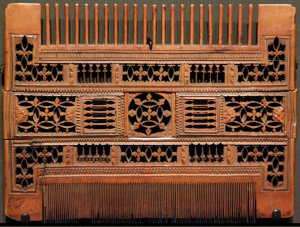

Sand had been a basic cleaning agent for centuries: for scrubbing floors, scouring iron cooking pots, and much more. This is easier to remember in German-speaking countries where the word Scheuersand, meaning scouring sand, is still recognised. Fine sand for cleaning gradually morphed into white abrasive cleaning powders with hygienic-smelling chemicals. There was an intermediate stage with sand and soda scouring mixes. One brand of “sand”, ATA, was remembered with nostalgia by some older people from former East Germany, after it vanished around 1989.

Household advice books from 100 years ago tell us about using the three esses. There’s one in German that recommends mixing soda and sand for cleaning wood – no soap as that makes wood look grey. Use all three for metal utensils but be sparing with the sand or you will damage tinned surfaces. Enamel is best cleaned with a soap and soda mixture, after soaking.

Or you can buy some detergent at the supermarket…..

Photos

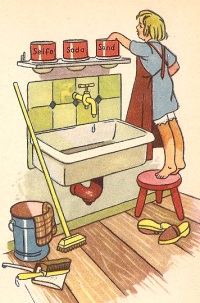

Photographers credited in captions. Links to originals here: first big picture, child’s book illustration, sepia photo. More picture info here