Wooden tubs with fine carving inside the lid were traditional containers for a few pounds of butter in parts of Norway and other Scandinavian countries. Some were beautifully finished on the outside too, and could be used to take butter to festive gatherings and serve it attractively.

Because the interior carving gave the top of the butter an attractive design, these were called butter moulds by the treen (woodware) expert Edward Pinto. Obviously they did shape and mould the butter, but English-speaking antiques experts today tend to call them butter tubs.

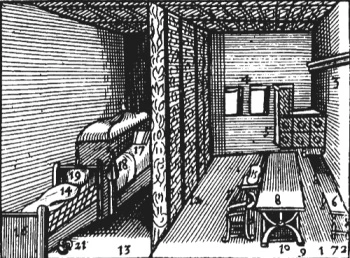

Decoration on the outside was carved or painted or burnt, or all three. Tubs were constructed in the traditional cooper’s way. Made in the same way as barrels or buckets, with upright staves braced by bands around them, these tubs had two pieces of wood longer than the rest. They slotted into the lid and had a hole for the pin that fixed top and bottom together. Loose joins were sealed with rushes.

Size, shape, date

Other tubs have a neater finish than the first one pictured here, with wood curving smoothly round the whole surface, using techniques like Swedish svepask. They all tend to follow the classic form: round, on three little legs, a characteristic handle on top integrated with the side fastenings. They are often about 20cm (8in) high and wide. Pinto says a typical container holds 4 to 6 pounds (2-3 kilos) of butter, though some might carry more.

None of the tubs illustrated here is dated but I guess they are 19th century. I’ve seen one from 1837 and the overall style fits in with these. This extra special one is from the 1830s.

Containers of this type were also used for carrying stews, porridge and other semi-liquid food. I’d like to know if carving inside the lid is a decisive clue to their purpose. Or was one container used for both purposes? This would break with the usual rule that dairy utensils are kept separate and scrupulously clean to avoid souring the butter.

Wooden porringers

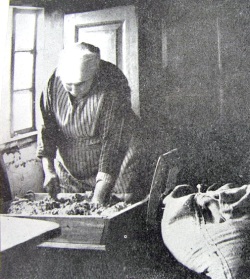

The Swedish container in the black and white picture is called a porringer (cooked food container) in a book by Charles Holme, who travelled to many parts of Europe to study, photograph, and write about “Peasant Art” – what we would call folk art now. It’s hard to know how much information he gathered about the everyday use of the items he studied. He was an art journal editor whose main interest was design.

As far as I can tell without knowing the language, the Norwegian name smøramber for these is closer to butter tub than to butter mould. Smør means butter. Amber doesn’t seem to be a common word in Norwegian. Interestingly, in medieval England an amber was a “vessel with one handle”, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and also a measure of liquid and dry weight. And while we’re looking at words, the dictionary says a porringer is a “a small bowl or basin, typically with a handle, used for soup, stews, or similar dishes.”

Photos

Photographers credited in captions. Links to originals: Colour photos by Rolf Steinar Bergli here and here. More picture info here